Last week HLTH drew over 12,000 people to Las Vegas across every niche and subculture of healthcare: from early stage to unicorn, from public health to medicine, from private sector to government. HLTH has gotten so big that it recently spawned a spin off and plans to take the conference to Europe in 2024.

This rapid evolution tracks the maturation of digital health as a whole. Over the last decade almost 2,000 health start-ups have collectively raised $77 billion in venture capital. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Health Assembly adopted its first global strategy for digital health. And just this weekend the editor-in-chief of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) tweeted that she is recruiting the journal’s first-ever digital health editor.

Skeptics maintain that the space is filled with more hype than substance, pointing to self-proclaimed disruptors who talk of change and progress while year after year healthcare just becomes clunkier. This sentiment is understandable. Few companies have actually demonstrated that their innovations are valuable: a recent study found no correlation whatsoever between venture funding amounts and “clinical robustness,” as defined by regulatory filings or clinical trials.

And at this moment, following a decade of sustained growth, the digital health industry is going through a crucible as the economy softens and excess capital dries up. Amid the usual evangelism, HLTH 2022 was markedly self-aware. There were panels that poked fun at declining valuations and bingo cards for the latest industry buzzwords.

Here’s what stood out to me: the good, the bad, and the ugly.

The good: Mainstage attention for women’s and family health

Before the sun came up over the Strip, Maven kicked off the week in Las Vegas by announcing our Series E round of funding, a strong sign that women’s and family health remains positioned to grow as a category despite mounting signs of recession. With large “up rounds” less common these days, the announcement was widely hailed as cause for optimism. On Monday afternoon, our founder and CEO Kate Ryder took the main stage alongside founders Anne Wojcicki of 23andMe, Toyin Ajayi of Cityblock Health, and Lux Capital investor Deena Shakir. It did not appear to escape anyone in the standing room only crowd that one of the most popular panels at the meeting was composed entirely of pioneering women.

The needs of women and families are hardly new, but in recent years recognition that these needs deserve to be addressed has become more commonplace among business leaders. As I told CNBC’s Jon Fortt that evening, family-building and maternity benefits remain firmly at the top of essential needs for reproductive-age employees. Even in a near future where labor markets relax, employers — and their human resources leaders — are very sensitive to bottom-up pressure. Years of pandemic era disruptions capped by sweeping restrictions to reproductive healthcare have amplified the discourse on gender and racial equity, and rightly changed the standard of care and support that people expect.

The bad: Entrenched incentives

“Value-based care” is among the terms that have earned buzzword bingo status. Despite the noble aspiration it just has less meaning in a world where companies can claim its mantel while still failing to make the populations they serve healthier.

The fundamental problem is that the healthcare system rarely centers its users. The driving incentives to make money remain far removed from what is needed to produce health. As a case in point, notoriously low net promoter scores among members have no discernable impact on the quarterly earnings of large health plans.

The specific conversation at HLTH was spurred, in part, by the well-timed blog from the Andreessen Horowitz team, arguing that the world’s biggest company would some day hail from healthcare. The authors argue that healthcare has never had a true consumer-oriented, tech-native player that was ready to bring a world-class user experience to the category. One opportunity, they wrote, is to combine the best of an Apple’s user experience with the analytical rigor of a UHG.

To which I would say: Yes, but.

An app alone cannot fix healthcare, perhaps because in healthcare, user experience encompasses a high degree of easily squandered trust. For many, healthcare is difficult to ‘use’ because it manipulates them into receiving unnecessary and often expensive care. It is difficult to use because their providers don’t always make them feel seen or heard. It is difficult to use because there is a culture of shame and stigma around asking for help.

Within women’s and family health, these challenges are particularly striking and the incentives often run in opposite directions. In fertility and pregnancy the financial pull is often toward potentially avoidable treatments like IVF or c-sections; in menopause, finances are a barrier that blocks care in the absence of strong revenue models, which is perhaps why 3 in 5 women who visit a physician because of their symptoms leave without being treated.

The ugly: Fear-based selling

There is, somewhere, a school that trains marketers to describe the absolute worst possible situation you might encounter should you choose not to purchase a particular widget. I get it. Being told we can avoid something terrible with a simple, affordable fix is attractive.

The problem — particularly in healthcare — is that this approach is manipulative, and often based on a shoddy interpretation of facts. The fertility space is rife with fear-based selling because for many people the prospect of building a family is existential. At HLTH, I heard one executive confidently declare they’d be taking their daughter to freeze her eggs — the moment she turned 18.

Fear thrives on misinformation and confusion. And the fact is undeniable that we are still woefully ill-informed about fertility and even pregnancy, a knowledge deficit that owes itself to historic lag in federal investment in women’s health research. But we know enough to know better — egg freezing, for instance, is not a benign procedure and hardly a guarantee of pregnancy. Moreover, there are many ways outside of high-intervention services to improve your chances of conceiving.

Fear-based selling works wonderfully in a fee-for-service ecosystem. When volume matters more than value, patients’ well-being is much easier to overlook. Fertility is this strange beast — a rapidly maturing field that clings to the old economic model. In 2023, my hope is twofold: that we start viewing it as healthcare, not a perk; and that we think more expansively about the fertility ‘episode,’ measuring our success on helping our patients bring home a healthy baby in the safest, quickest way possible.

The good: value still matters — perhaps more than ever

Despite the entrenched incentives, the predatory marketing, and the turning economic tides — women’s and family health continues to grow and the case for delivering better care at lower cost is as strong as ever. Thank you to the HLTH team for organizing such a broad gathering, and to all I met and re-met during my brief visit. This is an incredibly dynamic community, full of innovation, optimism, and well-founded skepticism, and I’m glad to be a part of it.

What my team is reading, considering, and building against

For those interested in where Maven is headed next, I encourage you to check out Kate’s blog post. For us as a clinical team, we are especially excited about the opportunity to invest in our care model for global populations pursuing fertility and family-building journeys, along with core work on social determinants and further integration with brick-and-mortar providers.

I’m proud of this newly published paper in the Journal of Hospital Medicine with my close collaborator and friend Avery Plough, which shares our perspective on why healthcare needs designers and charts lessons learned spanning our original work in hospitals to our latest work in digital health. As we write in the paper, poor design in healthcare is not just annoying. It’s dehumanizing.

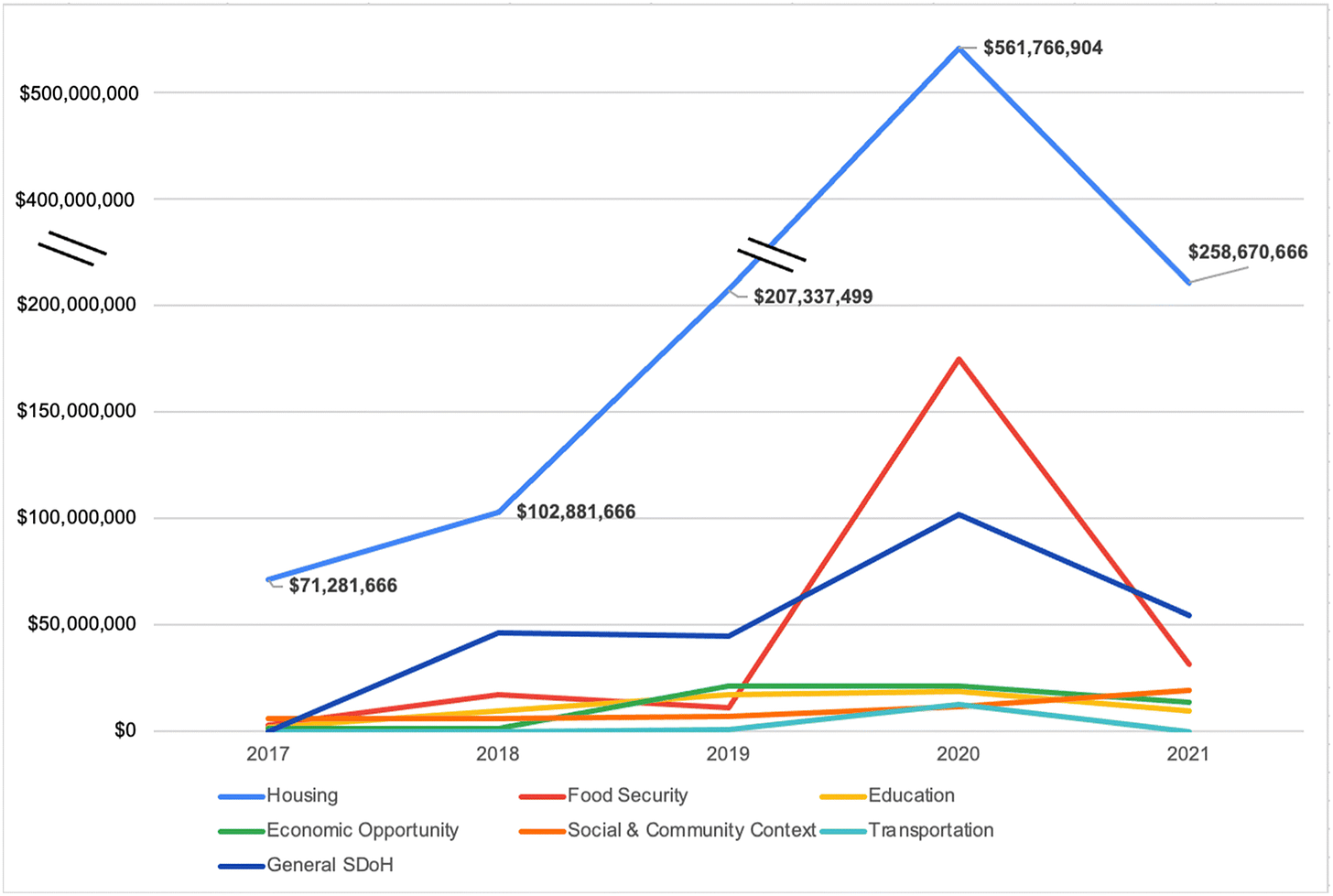

In the Journal of General Internal Medicine, researchers quantified the top areas of social services investment by private insurers dating back to 2017. Data show that 80% of health outcomes are attributed to social determinants like housing and nutritional food. In many cases these needs are not reliably detected. Even if they are uncovered, providers report a lack of time and resourcing to effectively address them. Our hope at Maven is that a digital platform can help with both assessing and addressing social needs and look forward to sharing our data on this soon.

One way that hospital quality is assessed is through the measurement of ‘never events,’ a standardized set of serious occurrences that should be preventable through conscientious practice — for example, using a contaminated oxygen source or causing a patient’s death through the use of the wrong medication. These ‘never events’ all relate to the practice of care; Dave Chokshi and Adam Beckman propose an expanded definition that includes never events for hospital policy. (The piece is relatively short and un-paywalled). What is compelling about this proposal is it correctly identifies a hospital’s administrative practices as core to its perception by patients. When we speak of healthcare’s ‘trust crisis,’ this element is often missing. A hospital that underpays its employees, underinvests in its communities, or aggressively pursues payment from those who can’t afford it undermines its ability to effectively serve as a locus of care.