Fertility After Roe

We must accelerate the shift from fertility as luxury to fertility as healthcare

Before the SCOTUS decision overturning the right to access an abortion, legal and public health scholars argued that the “full spectrum” of reproductive health hung in the balance. Now, with the decision rendered, new and disturbing data underscore why.

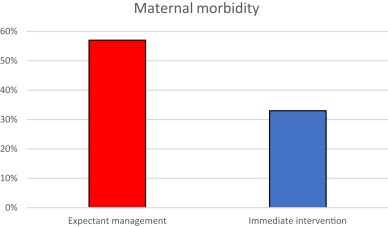

In Texas it has become a felony for a physician to administer medicine that ends a pregnancy, creating a perilous clash between dogmatic legislators and the complex realities of obstetric practice. In some cases continuation of a pregnancy can be life threatening for the mother. Last month, two inner-city Dallas hospitals reported that since the felony law was enacted, among 28 such emergencies nearly one in three pregnant people became so sick that they required admission to the intensive care unit.

As similar cases mount across the country, it is increasingly apparent how restricting abortion impacts maternal health. Public attention has been rightly centered on how women and pregnant people are cared for. However the fertility industry has largely skirted scrutiny amid the shifting policy landscape. In some cases, industry leaders have claimed that anti-choice legislators don’t really have it out for IVF, and that “personhood” laws ultimately will either not pass or not be enforced upon embryos.

This business-as-usual thinking is irresponsible. America already has a maternal mortality crisis. Now, across large swaths of the country, high risk pregnancies are even riskier. Whether or not the practice of in vitro fertilization (IVF) remains legal, the personal risks of what comes after fertilization have significantly increased. That basic truth demands a reassessment of the current approach to fertility and pregnancy, one that too often treats the former as a luxury and the latter as an afterthought.

Proactive and reactive fertility care

In cataloging massive expansion of the fertility industry, Dr. Lucy van de Wiel describes a frameshift in clinical approach, wherein fertility transformed from a “reactive” to “proactive” specialty. Where once IVF might be considered only as a last resort to help someone become pregnant (so-called “reactive” care), the emergence of fertility as a sponsored benefit has opened up the possibility of a more proactive approach, where generally healthy patients turn to clinics to preserve their ability to have children in the future and IVF is more of a frontline intervention for couples trying to conceive.

Neither model is ideal.

In ‘reactive’ fertility care, a couple might suffer alone for months or years, unsure of whether something is wrong or what can be done to help. The ‘reactive’ model exacerbates the painful stigma attached to infertility journeys, where people bear their burden in silence and isolation (fertility is rife with examples of patients having their symptoms dismissed and their feelings ignored — particularly for Black women). In many cases the reactive approach to fertility parallels the shortcomings of our healthcare writ large, where medicine is often late, expensive, and stressful for patients and their loved ones.

A proactive approach increases availability of fertility services but quality does not automatically follow. In an overly proactive model patients may undergo demanding and risky courses of treatment before they really need them, driven by their own concerns about becoming pregnant, some savvy marketing, and the fact that it’s available as a benefit. At the same time, the sponsor of fertility benefits may unwittingly be financing overutilization of a service associated with higher risks of pre-term births and other adverse outcomes, care for which is becoming more challenging in a post-Roe world.

Establishing a meaningful definition of quality

Every person deserves the choice and the opportunity to build their family with dignity. This requires a fertility industry that is held accountable for providing the shortest possible pathway to bringing home a healthy baby — affordably and safely. Today, we are far from this vision.

Even with wider availability of fertility benefits, IVF remains primarily for the wealthy, with most people paying out of pocket for some or all of their treatment. The average cost of a single ‘cycle’ of IVF — beginning with the artificial stimulation of a patient’s ovaries to produce eggs and concluding with the transfer of an embryo to the birth parent’s uterus — is well over $25,000 (and most people who utilize IVF receive more than one cycle). At the same time, like much of healthcare, cost and quality of care are not well correlated. IVF clinics make money for running tests and doing procedures, regardless of the outcome.

In the current state, pregnancy outcomes are largely attributed to the ob/gyn or delivering hospital, and agnostic to the role of the IVF clinic in supporting low risk pregnancies. This does not make sense. Around the world, IVF clinics perform nearly 2.5 million cycles and set the course of 500,000 pregnancies each year. They are positioned to influence birth outcomes in myriad ways. They could help as many people as possible avoid IVF in the first place with accurate diagnoses (our SVP of Brand and Communications came to Maven after multiple failed IVF cycles only to learn that what she actually needed was a $5 thyroid medication). And when IVF is needed, clinics could and should of course follow best practices in inducing ovulation, retrieving eggs, and in selecting and transferring embryos.

Towards value in fertility care

Everyone benefits from minimizing the likelihood of high-risk pregnancies. For this to actually happen, those who sponsor and administer fertility benefits must drive accountability. This requires a way forward that is neither reactive nor overly proactive, one that uses data and evidence to meet each person’s personal family building needs.

Providing a nuanced, personal approach to fertility care can be complex. That being said, knowing what good care looks like and demanding it should be simple — and delivering it is well within the fertility industry’s capability. Approaches that end with a fixed IVF cycle and fail to take responsibility for what happens to the pregnant person and their baby afterwards should be unacceptable.

Good care should not blindly drive utilization. Our team at Maven measures natural conception rates alongside IVF rates, and we scrutinize our fertility and maternity outcomes in tandem. We do not conflate inclusivity with health equity, and appreciate that access matters only as a means to a valuable end. Most importantly, we position IVF as part of a continuum of reproductive health care rather than as a point solution.

—

What my team is reading, considering, and building against

A story in the August 8 issue of Businessweek (which as a whole is devoted almost entirely to the post-Roe landscape) highlights the anguished calculations of couples across the country as they consider what abortion restrictions will mean for their desire to have a family via fertility treatments including IVF and IUI. The article highlights the tradeoffs that are already inherent in this space between cost and likelihood of achieving pregnancy, as well as the ways in which people are being influenced to choose pathways based less on what gives them the utmost chance for a healthy baby and more for what fits into the constraints of time, money, and potential legal liability. Anyone who cares about healthcare in this country should be enraged that the best interests of patients are being structurally deprioritized.

After Dobbs, more than a dozen state ‘trigger laws’ went into effect, including that of Georgia. In addition to being a so-called ‘heartbeat bill’ that bans abortion after 6 weeks’ gestation, the law establishes a 6-week-old embryo as a person with full legal rights. As we have seen in a few instances, most notably with the viral story of a woman’s fetal defense for using the HOV lane in Texas, personhood laws point the way towards numerous unprecedented legal scenarios that will have a profound effect on healthcare, to be certain, but also day-to-day life. Because of Georgia’s personhood provision, the state will now permit “any unborn child with a detectable human heartbeat” to be claimed as a dependent, which provides a $3000 tax exemption to the household. How will parents-to-be go about registering their fetus with the state and keeping them abreast of any developments during the ensuing eight months of pregnancy? TBD. Says the Times: “Specific instructions on how to claim a fetus on a tax return are expected later this year.”

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation released data showing that just over 20 percent of Black and Hispanic adults report being the same race as their healthcare providers compared to nearly three-quarters of white adults. In uncoupling access to care from physical location, digital health should make it more possible for people to receive care from those who share their lived experience. Ultimately however, we need to support Black and Hispanic people in entering the health professions and we must sustain that support at every step of the long training process.

A survey on social determinants of health found that nearly all physicians report their patients are impacted by at least one factor, most commonly financial instability and transportation access — and that they feel ill-equipped to support these needs and burnt out when they even try. At the same time, the vast majority of surveyed physicians want to do more for their patients, demonstrating once again that burnout is not caused by hard work. Rather it is caused by the disconnect between the job you want to do and the job you are positioned to do. By expanding availability of care and support outside of the narrow 15 minute appointment window of brick and mortar settings, digital health should be able to help here, too.

A study in the Green Journal examined catastrophic health expenditures among pregnant people through the first year of their child’s life. The authors found that birth parents were at higher risk of catastrophic health expenditures than non-pregnant people of the same age, and that some low-income families spend close to 20% of their annual income on medical costs during the time period. We can all do this math and know how significant a burden this represents. The study also showed that patients with coverage through Medicaid had meaningfully improved finances — yet one more datapoint showing how expansion is critical in addressing our maternal health crisis.

i help women get pregnant, stay pregnant and have healthy babies naturally: https://fertilitywhisperer.substack.com/p/a-brief-look-at-the-history-of-traditional

FertilityWhisperer

Writes Fertility Whisperer's Substack

1 min ago

I help women get pregnant, stay pregnant and have healthy babies! check out holistic fertility modalities here: https://fertilitywhisperer.substack.com/p/a-brief-look-at-the-history-of-traditional