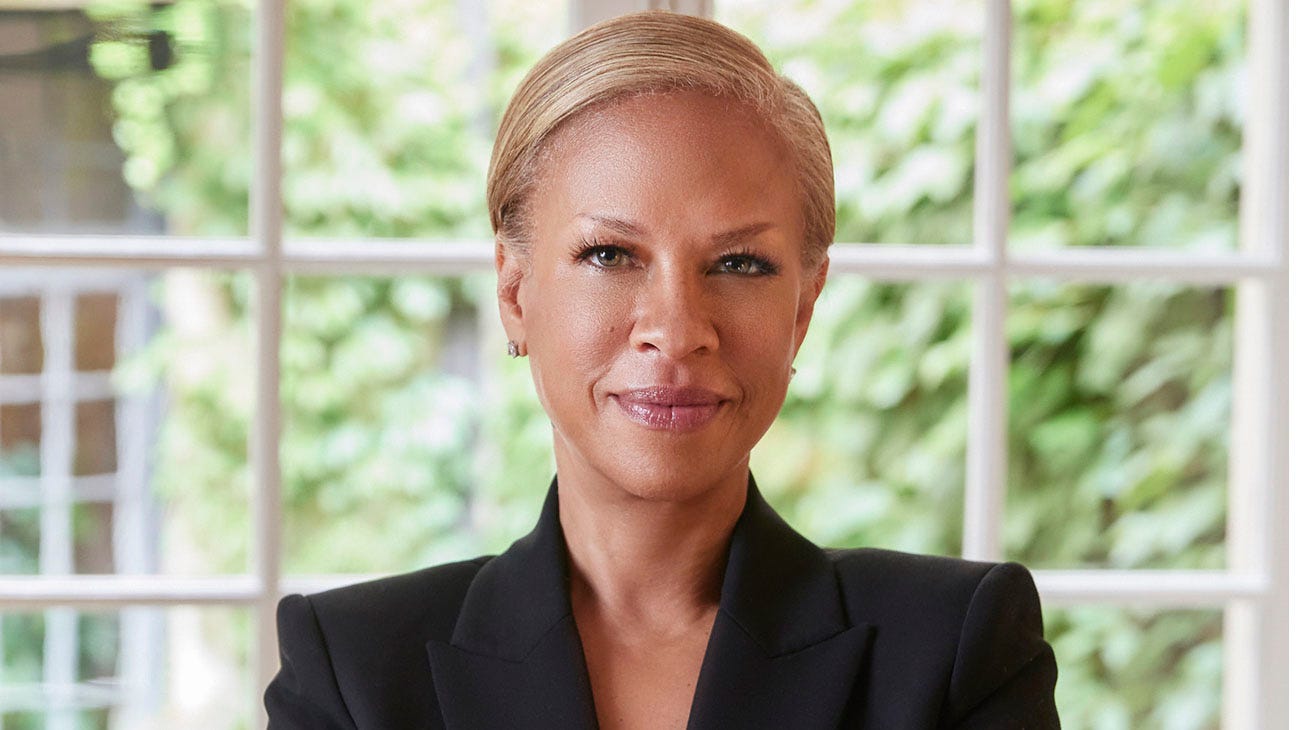

Tonya Lewis Lee on the pain—and power—of her documentary “Aftershock”

Experts have reported on the Black maternal health crisis by the numbers. But what about the families behind those numbers? That’s where we turn to film.

The first time I met Tonya Lewis Lee was during the pandemic, on Zoom, and I did not know who she was. She and her co-director Paula Eiselt told me they wanted to make a film about maternal mortality in the United States.

As an obstetrician and professor, I am asked often by the media to comment on terrible statistics—that Americans today are 50% more likely to die in childbirth than their own mother; that those risks triple for Black people. With all this necessary reporting comes a lot of accompanying doom and gloom.

But, from the beginning, Tonya wasn’t interested in doom and gloom. She wanted to showcase solutions. She began with a foundational premise: that the most important answers lived not in the ivory tower but in the wisdom of communities. Without knowing exactly where it would lead them, Tonya and Paula decided to follow two extraordinary families who had experienced the worst, picking up where much of the traditional media had stopped reporting.

In October 2019, 30-year-old Shamony Gibson died 13 days after the birth of her son. Just six months later, in April 2020, 26-year-old Amber Rose Isaac died of an emergency c-section. Their losses—as mothers, and daughters, and friends, and partners—touched every corner of their communities, leaving behind an organized and energetic collective in their wake.

By following their families, Tonya and Paula chronicled the formation of a revolution in real time. The resulting film, Aftershock, is timely for the current moment and an evergreen watch for Black History Month. And you don’t have to believe me—just ask the Sundance Film Festival, the Essence Film Festival, the Peabody Awards, the duPont-Columbia Awards, the Creative Arts Emmys, or its current distributors, Hulu and Disney+.

Tonya Lewis Lee told me she always wanted to be a storyteller, though first she became an attorney. When she did finally find her way to filmmaking—through her work in civil rights, her lifelong support of the arts, and later, her husband Spike Lee—she brought with her the hallmarks of a public advocate. I’m lucky to have worked with her on Aftershock, and on the tailwinds of the film’s latest round of accolades, even luckier to have Tonya join me in conversation about it:

You have a long history of advocating for new mothers and infant health. You even had a partnership with the Department of Health. Can you talk a little about how that came to be?

Back in 2007, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services asked me to be the spokesperson for an infant mortality awareness raising campaign here in the U.S., called “A Healthy Baby Begins with You.” They reached out to me because I had written a couple of children's books with my husband—”Please, Baby, Please” and “Please, Puppy, Please.” And initially, my first year, I didn't realize that the statistics were very similar to that which we see in maternal health, where Black babies are dying at three times the rate of white babies. That it didn't matter what your educational or socioeconomic background was.

In the second year of the campaign, we started going into communities, everyone coming together all hands on deck to talk. It was really fantastic for me to meet the amazing people out there who do the work day to day, for very little shine and very little coin. I would return home hopeful because there are good, amazing people in the world. I was with that campaign for almost 15 years. Now I will forever, always be advocating around women's health.

Let’s talk about Aftershock. During the filming, I was mostly just excited you wanted to make a film on this subject. Then, when I saw the first screening of it at Sundance, I was blown away, as everybody who sees it is. The authenticity with which you capture people is extraordinary. How did you decide that you wanted to embark on this multi-year journey?

Through the campaign with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, I had made a smaller film for them called “Crisis in the Crib,” about the infant mortality crisis. But inevitably, while I was hearing about infant deaths, I was also hearing about maternal deaths. And then I want to say it was like 2018 that Linda Villarosa wrote a big article for The New York Times. I was really happy that she uncovered the story in that way, and it inspired me because I was like, I need to hurry up and make this film, or I knew that somebody else would do it.

Then I was at a conference and saw this woman with a film crew. And someone was like oh yeah, she's working on a documentary on the maternal mortality crisis. So I went over to her and introduced myself. A week later, we met for coffee, and discovered that we really had a shared vision in how to tell this story. And so Paula Eiselt became my partner.

Part of what made your documentary really special is you embedded with the people in it, and you filmed longitudinally over a period of time. It feels like that took an amazing leap of faith for everybody involved. Did you know that would be your approach from the outset?

Yes. We both knew we wanted to follow the people who had experienced the loss. Paula saw Shawnee Benton Gibson on Instagram, whose daughter Shamony had passed away. Shawnee had put out a communal invitation for a celebration of life for Shamony. Paula called Shawnee up, Shawnee answered and said, yes, come. I mean, this is two months after her daughter had passed away, she allowed us to film. So it was a leap of faith, for sure. But I will say I think it's important for people to know your heart and your work a little bit. I've been in this space a little while. There was no way that we were going to do anything to Shawnee, Omari, and Bruce that wasn't respectful and thoughtful and I think they knew that.

Shawnee Benton Gibson, surviving mother of Shamony Gibson, and Bruce McIntyre, widow of Amber Rose Isaac, are just two of the family members Aftershock spotlights.

Most media attention about the Black maternal health crisis is about the events leading up to the deaths. Nobody really talks about what happens to the families and the communities afterwards. Was that your intent from the beginning as well?

The intent was to closely follow the people who were left behind, but we didn't know what we were going to really get at all. And then, meeting Shawnee and Omari, I mean, and just the way they work through the world was, again…that's God. They're amazing people. We also knew, though, that we had to strike a balance between giving medical and scientific information, and following the family. And really from the beginning, we knew we wanted to ground this in, like what happened? What has happened historically to get us to this place today? And we also knew we had to inspire.

To paint the picture, there was a moment in the filming process where we’d ended up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It was the middle of the pandemic. It was the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacres. And we’re trying to get into hospitals, to film, and I’m trying to barter those connections without stepping on any toes. I remember you turned to me and you said something like, we are standing on the bones of these victims.

Yes. Literally, while we were there, they were digging up bones from the graves of the massacre. These issues are hard. And, it’s scary because there are consequences. We do live in a world that I see as still being very anti-Black, historically and still today. A lot of those people specifically in Tulsa, you know, they are ancestors. And when I say ancestors, I don't mean like, great, great, great, great. I mean, like, grandfather, great grandfathers were involved…parents. They know who committed those crimes. They know what happened there.

Something I think a lot about here in my work is, how do we tell these stories without only dwelling in the doom and gloom? How do you balance that as a director?

I think Aftershock sort of rang the alarm in a way that said, yeah, you're not crazy. This has been happening. And this is why, and there is hope. For me now going forward, I really think a lot about the fact that many people know about this crisis, and how hard it is…so how do we turn the conversation to a place where we are truly empowered by the information?

I was just talking to someone this morning, who was saying to me, that they had a pregnant friend who watched the film and that she came away feeling empowered. I've heard that there are Black families who are afraid to have children because of the statistics that we're living with. But, we show an amazing birth in the film, Felicia’s birth, which happened in Tulsa. I hope people will come away feeling like, okay, I can be the captain of my birth journey. I don't have to just be a passive participant. But I still think there's a bigger way to be talking about the issues, so women realize the true power that we have, both when we birth, and especially when we reclaim that rite of passage.

In lieu of our usual list of favorite reads, I’m just gonna say: sign into Hulu and watch this movie. It is well worth your time.

The documentary website includes a screening event kit, discussion guide, and a list of ways to take action.