Healthcare's New Imperative

'Follow-through' innovation and what it means for one of the world’s most commonly utilized health services

During the BBC Reith Lecture in 2014, my mentor Dr. Atul Gawande contrasted the last century of medical innovation with the current one. He pointed out that we have had remarkable breakthroughs that vastly extended what we know how to do. And yet, the dominant cause of suffering in the world is no longer lack of knowledge — it’s lack of execution.

This disconnect has never been more evident or more painful. The first mRNA vaccine against COVID-19 received emergency use authorization within a year of identifying the virus. However, amid a fragmented delivery system and rampant misinformation, actually getting shots into arms has proven to be a far more daunting task.

Dr. Gawande introduced the concept of “follow-through” innovation as a new imperative for healthcare, recognizing that while medical breakthroughs will always be necessary, they’re not enough to address the primary failures of our industry. Fundamentally, the promise of digital health is to ensure we are following through on what has been proven to work by delivering care in new ways.

In this issue of The Preprint, I speak with two scientists who are applying follow-through innovation to reimagine one of the the most commonly utilized health services: prenatal care.

Dr. Alex Peahl is a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Michigan and longtime collaborator of mine, who was selected as Maven’s first visiting scientist.

Rebecca Gourevitch, is a PhD candidate in health policy at Harvard University, who has worked closely with both Alex and I over the years.

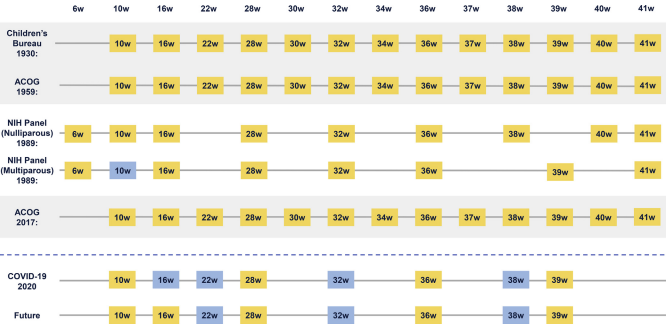

The current U.S. approach to prenatal care was established in 1930. Despite all the technological advancement in lab testing, ultrasounds, and digital access, prenatal care hasn’t changed in all this time. Your great grandmother had the same prenatal care model that you do — because breakthrough technology did not translate into follow-through changes to the health care delivery system.

Emerging studies show we can safely deliver care with fewer in-person visits, more digital support and potentially greater impact on pregnant people’s health. I talked with Alex and Rebecca about their research, and what it implies about what better looks like. The below is an edited excerpt of our conversation (I’m the italics).

Rebecca, you have questioned the way our field has been measuring the quality of prenatal care. What does quality prenatal care mean?

RG: Historically prenatal care quality has been measured by two features: how far along you are in your pregnancy when you start care, and then the number of visits that you have after you start care. Both of these are important, but they certainly don’t capture the whole picture.

In my work, I try to think about different ways that we can measure prenatal care quality: do you get the recommended medical services that you’re supposed to get during your pregnancy? Does the care that you receive during your pregnancy succeed in promoting healthy birth outcomes for you, the pregnant person, and your baby?

Those are more medical, but there are other components of care quality worth considering: Do you receive the necessary guidance and social support? Part of what we do in prenatal care is prepare people to experience the rest of their pregnancy, to labor and deliver, and to be parents to a newborn. And receiving that support is really important.

Part of care quality is also in the eyes of the patient: Are you satisfied with your care? Was your prenatal care delivered in a way that was respectful? That was culturally appropriate? That was empowering? Take all of this together and it would give us a more complete picture of prenatal care quality.

Alex, as someone who is both thinking of prenatal care from a health services point of view and through directly caring for people, what are the gaps in the Children’s Bureau original prenatal care model? What are people not getting?

AP: When it comes to prenatal care, we are well equipped to provide medical care. We have the tools to deliver care for high acuity, complex patients, for babies that have complex congenital anomalies and need fetal surgery. But in my experience we are not as good at exactly what Rebecca just highlighted: providing patients routine guidance and social support, and thinking about how to best deliver care in line with patients’ preferences.

In 1930, the model was created to detect pregnancy complications, not to promote wellness or even joy during this exciting moment in our patient’s life. Most of us are trying to deliver prenatal care in a 10-20 minute visit. That doesn’t provide a lot of time for us to give support or education. A lot of times this leaves patients really unsatisfied without their needs being met. It’s a tension I face as a provider all the time.

The other piece that we’ve alluded to is social and structural determinants of health. We know that 40% of health outcomes can be attributed to social determinants and yet we are not regularly screening for these or managing them in prenatal care practice. When maternity care professionals do identify [social needs], often their reaction is to schedule more prenatal visits, which may exacerbate the barriers that patients face, particularly if they include things like transportation or employment. We paradoxically ask patients to come to our clinic more, which creates a higher barrier to care.

Rebecca, you recently published a paper exploring that first set of alternative quality measures you mentioned — the contents of the visit. What did you find? (Disclosure: I served as senior author on this paper with Rebecca and a team from OptumLabs and Harvard University.)

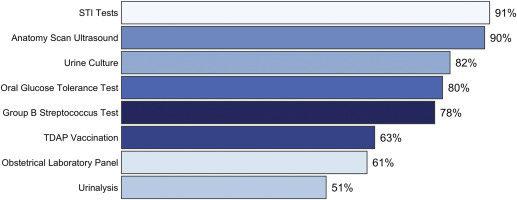

RG: Instead of looking at how we’ve traditionally measured quality — when care starts and how many visits you have — we looked at whether patients are receiving these services that are universally recommended for all pregnant people. We looked at 8 of these services in particular, things like screening for gestational diabetes and Group B strep, and Tdap vaccination. What we found is that, on average, members of this population received only 6 of the 8 services, and importantly, the number of prenatal visits was not a strong predictor of receiving these services. Patients were just as likely to receive that average amount of recommended care if you have 6 prenatal visits or you have 16. And this really emphasizes that measuring prenatal care quality by the number of visits masks a lot of gaps in actually receiving services in the way you’re supposed to.

We also find really concerning patterns of variation in who is receiving these services across the population. For example, in our sample about two-thirds of people receive the Tdap vaccination when they’re supposed to, but rates of Tdap vaccination are much lower in predominantly Black communities, or predominantly Hispanic communities. This points to some of those social and structural determinants Alex was talking about, including racism, that we can’t directly measure in our study. These findings speak to why improving quality measurement is really important, especially in this context of maternal health, when we know the disparities in outcomes are so severe.

Alex, you’ve been thinking about what this alternate model should look like and you recently published a paper about a model you established at Michigan. Can you tell us more about that?

After the acute pandemic, we launched a model called the Michigan Plan for Appropriate Tailored Healthcare in Pregnancy, which shares its name with new national recommendations published by our team in collaboration with the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. The local version allows patients to choose their own path in three main areas that Rebecca and I have referenced throughout this conversation. With medical care, patients are able to choose a hybrid model with virtual and in-person visits or entirely in-person care.

If patients choose virtual care, they must have a blood pressure cuff at home to ensure the quality of virtual and in-person visits is the same. Patients can choose from a robust list of education resources, online and in print. We have community resources as well as a local online pregnancy support program that combines mental health and wraparound social support for our patients. We talk about each of these components right from the moment the patient calls to schedule their first prenatal appointment, which emphasizes that each of these streams is just as important to their prenatal care journey.

We’ve talked about improvements you’ve both helped drive in our understanding around quality and delivery of prenatal care. Pull out your crystal ball for a second. What’s the ideal of a prenatal care model going forward?

RG: I think what Alex described, having options as a patient, is a big improvement over the status quo. Part of what will need to happen alongside that is developing quality measures to make sure that, regardless of which of these paths you choose, or who you are, or where you’re getting your prenatal care, your care is consistent with a certain standard. That standard of care should include both the medical services you’re supposed to receive as well as the anticipatory guidance and social support that we keep talking about.

In healthcare, quality evaluation is a delicate balance. You don’t want to measure too much so that everyone is doing a robotic sort of medicine. But you don’t want to stop measuring it, either, because then things can be getting worse and you won’t know. Finding this balance between letting people pick their own path while keeping this standard of quality is going to be the next frontier.

AP: Rebecca and I are peeking into the same crystal ball. As we were designing our model at Michigan, we interviewed patients in Detroit, in a predominantly Black, low-income community, asking what they wanted from prenatal care. Our patients told us they wanted to choose their care experience, the one that’s right for them. They wanted a robust team of people supporting every aspect of their care, but they wanted that team to be led by a kind, compassionate, respectful maternity care clinician, who could connect them to services and answer their questions. They wanted a safe place to live and good food to eat, and, importantly, a supportive community to celebrate their pregnancy and their new child with.

It’s important to build a system for pregnant people, by pregnant people. Many of the issues with our current system are because we have this top-down system of care where we decide what our patients want.

—

What my team is reading, considering, and building against

This, from Nature on the protective power of vaccines for pregnant people, is stunning. Based on data from nearly 20,000 pregnant women in Scotland, the authors find that the risk of both serious illness and death was orders of magnitude greater for the unvaccinated. Three-quarters of all infections, 91% of all hospital admissions, 98% of all critical care admissions, and all baby deaths occurred in pregnant women unvaccinated at the time of their COVID diagnosis. And yet vaccination rates in Scotland, in the United States, and around the world continue to considerably lag availability. It is so, so important that we not give up our efforts to address vaccine hesitancy, and do so in an empathetic way that addresses people’s concerns and fears.

Underscoring Alex and Rebecca’s call to integrate social needs in prenatal care, a new paper in the Green Journal shows that more than 20% of all pregnancy-related deaths are due to homicide, suicide, or drug-related factors. The authors find that patients are at higher risk of suicide or drug-related death in the postpartum period, and homicide while pregnant, data that highlights how the maternal health crisis intersects with broader sociocultural crises like gun violence, partner abuse, and the opioid epidemic, and the importance of longitudinal, holistic support through the fourth trimester and beyond.

This is a level-headed and ultimately optimistic piece from the National Academy of Medicine on the state of digital health two years into the pandemic, that also happens to include an excellent reference to Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner: ‘Water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink.’ They point out that, “Despite nearly complete digitization of health care data… [we] expended far more effort than should have been necessary to quench thirst for high-quality actionable data.” The authors point to a future where a more efficient digital infrastructure allows patients to take full advantage of the rapid advancements now underway in all pockets of healthcare, from clinical trials to care delivery.

A great paper is one that produces lots of interesting questions, and this piece from Angela Cools is definitely that: her research shows that “U.S. women with an infant during an election year are 3.5 percentage points less likely to vote than women without children; [and] men with an infant are 2.2 percentage points less likely to vote.” That result is not surprising in itself — parenting an infant is a very busy and unpredictable time. The author offers that mail-in voting would help these parents and caregivers stay engaged in the political process, which also makes a ton of sense. The piece also surfaces for me how important it is to meet people where they are with critical services, particularly during the phase of life when they are building their families. In theory, this is the true promise of digital health. More to the point of the paper, I also start to wonder what happens to a society where this demographic isn’t able to voice its perspective at the ballot box election after election.

Finally, new research published in Health Affairs examined 18,000 electronic medical records and found that patients who are Black were described negatively in the health and physical (H&P) note at 2.54-times the rate of white patients, even when researchers controlled for socioeconomic and health-related factors.

The H&P is shared widely between practitioners and members of the care team, which means that one episode of care — one interaction between a patient and a provider — influences the next interaction. A patient perceived as “aggressive,” “challenging,” or “non-compliant” is permanently labeled as such, impacting in ways large and small — and consciously and unconsciously — how they are cared for by their providers and the system as a whole. To us, this highlights how digital health can have a compounding effect on racism if we are not intentional about mitigating bias at its source.

Anticipatory guidance and providing access to social services is mentioned briefly, but in a piece about the prenatal care model needing to be reset, breastfeeding education should at least be mentioned. This is just my opinion but prenatal breastfeeding/parenting education should be SOC.

@Neel: Our IBCLC founder and team have created a mobile app that provides personalized automatic lactation support on a broad scale (over 100,000 consultations answered each month automatically) and AI is in advanced development. A clinical trial research to quantify the increase in breastfeeding rates in the user population as well as how much costs it saves to the healthcare system is in progress and will be finalized later this year. It would be a pleasure to connect and talk about Maven Clinics plans to scale: https://www.linkedin.com/in/christiane-gross/

@Tara: thank you for all your fantastic help, always!